Despite strong local support for protection of this area, the proposed Rio Grande del Norte National Conservation Area Establishment Act is moving through Congress slowly. Garrett VeneKlasen with Trout Unlimited, talks about the need to push for the protection of our most cherished public lands for the benefit of our children and grandchildren. From the Albuquerque Journal (March 17, 2012):

Despite strong local support for protection of this area, the proposed Rio Grande del Norte National Conservation Area Establishment Act is moving through Congress slowly. Garrett VeneKlasen with Trout Unlimited, talks about the need to push for the protection of our most cherished public lands for the benefit of our children and grandchildren. From the Albuquerque Journal (March 17, 2012):

Everyone has a story and everyone has history. Tragically, most of us have lost or somehow forgotten important pieces of our story in the passing of generations. Some have a name for this – they call it “progress.”

New Mexico is one of the few states in our union that has a complete historical and cultural record with unbroken ties back to the origin of its traditional, land-based cultures. This epic tale – which is steeped in diversity, tradition and heritage – starts something like this:

In the beginning there was nothing but an endless expanse of wild and pristine country completely devoid of humans. Then perhaps 13,000 years ago, a small band of Paleoamericans, the Llano Culture, appeared in our story. And so began the rich cultural history of man upon the wild New Mexican landscape. Over time, the pueblos evolved, followed by Francisco Coronado and his fellow conquistadors, who first explored the Rio Grande Valley in 1540. Like the tribal peoples who came before them, the Spanish settlers who followed and remained upon the untamed land were soon irrevocably transformed by it.

New Mexico’s historical record is a sacred text that begins with one word – wilderness! Our state’s remaining wild places are irreplaceable, iconic cultural heirlooms. Wilderness is the genesis of New Mexico’s story. It is the first sentence in the first chapter of our epic tale; it is undeniably the sacred cornerstone of New Mexican culture. And these last vestiges of New Mexico’s wild lands must be preserved, honored and protected.

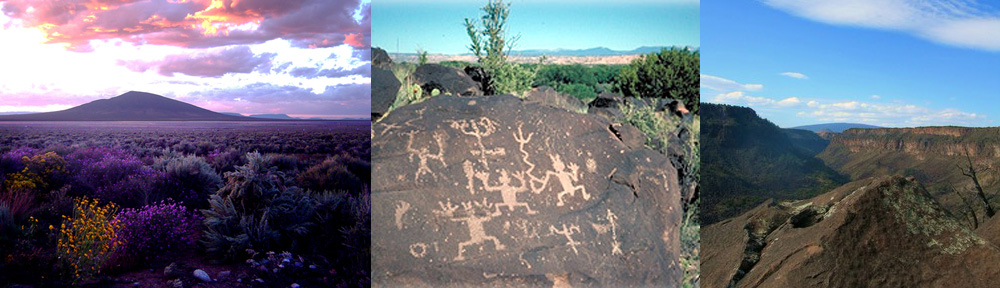

Of these sacred lands, I cannot think of two more worthy of protective designation than the Columbine Hondo and El Rio Grande del Norte, both in the northern part of our state. The Columbine Hondo is only 46,000 acres of rugged, critically important alpine headwater terrain in the Carson National Forest. The Rio Grande del Norte corridor, comprising approximately 236,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management lands, is the very heart and soul of northern New Mexico’s traditional cultural agrarian epicenter.

The focal antihero in this saga is time. Time is running out for our wild lands. Some members of Congress would love to see these currently unprotected lands either sold off to private hands or developed in the name of “prosperity and progress.”

As we speak, there are a host of bills in Congress cleverly designed to pillage the last pockets of unspoiled backcountry. If they pass, the beginning of New Mexico’s epic tale could someday soon be replaced with Chinese pulp mills, exclusive “ranchette” subdivisions, strip mines and clear cuts. Considering the political agenda of an increasingly ideologue-led Congress, the reality of this is much more plausible than one might think.

Just 472 years ago, nearly the entire landscape of New Mexico was wild and untamed. Back then, our Native peoples and Spanish settlers were peoples of the land. These cultures are so solidly rooted in wilderness that the two simply cannot be considered as separate entities.

Despite the odds, relics of the “original wild” still exist in isolated islands within the state’s ever-expanding sea of development and modernization. Our generation, through a local community and citizen-based federal legislative process, has a unique opportunity to protect these places so that future generations might have a direct tie to their past.

We owe this push for protection on our most cherished wild public lands to our children and grandchildren. Without a solid connection to their cultural past, how can they forge a meaningful future? As part of a diverse, bipartisan coalition of stakeholders – ranging from tribal interests, land grant concessions, grazing permittees, community leaders, businesses, sportsmen, homeowners, and conservationists – we have stood up in support for the protection of these precious lands.

I urge all across the state, regardless of political affiliation or personal self interest, to encourage our congressional delegates to protect the Columbine Hondo and Rio Grande del Norte now or risk forever losing your cultural and biological integrity in the name of “progress and prosperity.”